Phil 2:3

Be devoted to one another in love. Honor one another above yourselves.

Romans 12:10

Let us not become conceited, or provoke one another, or be jealous of one another.

Gal 5:26

And further, submit to one another out of reverence for Christ.

Eph 5:21

Finally, all of you, be like-minded, be sympathetic, love one another, be compassionate and humble.

1 Peter 3:8

For if anyone thinks he is something, when he is nothing, he deceives himself.

Gal 6:3

Some time ago Theudas appeared, claiming to be somebody, and about four hundred men rallied to him. He was killed, all his followers were dispersed, and it all came to nothing.

Acts 5:36

Do not deceive yourselves. If any of you think you are wise by the standards of this age, you should become "fools" so that you may become wise.

1 Cor 3:18

I have made a fool of myself, but you drove me to it. I ought to have been commended by you, for I am not in the least inferior to the "super-apostles," even though I am nothing.

2 Cor 12:11

As for those who were held in high esteem--whatever they were makes no difference to me; God does not show favoritism--they added nothing to my message.

Gal 2:6

Caution Against Over Self-Estimation

John Brown, D. D.

Galatians 6:3

For if a man think himself to be something, when he is nothing, he deceives himself.

These words admit of two different interpretations, according as you connect the middle with the first or with the last clause.

1. If we connect the middle clause with the first one, as our translators have done, the meaning is, If a man think himself to be a Christian of a high order, while he either is not a Christian at all, or, at any rate, a Christian of a very inferior order, he commits an important mistake and falls into a hazardous error. The man who supposes himself arrived at the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ, when in reality only a babe in Christ, deceives himself, and throws important obstacles in the way of his own improvement. In their own estimation they have little to learn, while the truth is, they have learned but little. But the mistake is much more deplorable when a man flatters himself into the belief that he is a Christian, perhaps a Christian of the first order, while in reality he is not a Christian at all. The thing is quite possible — I fear not uncommon. We pity the poor maniac mendicant who thinks himself a king; we pity the man who has persuaded himself he is a man of wealth, while in reality he is in immediate hazard of bankruptcy; we pity the man who is assuring himself of long life, when he is tottering on the brink of the grave; but how much more to be pitied is the man who thinks himself secure of the favour of God, and of eternal happiness, while in reality the wrath of God is abiding on him, and a miserable eternity lies before him! No kinder office can be done to such a person than to arouse him from his state of carnal security, to undeceive him, to convince him of his wants while they may be supplied, of his danger while it may be averted. A woe is denounced against such as are thus at ease in Zion.

2. Perhaps, however, the apostle's meaning is, "If any man think he is something, he deceiveth himself, for he is nothing." The apostle is cautioning the Galatians against a vainglorious disposition; and in this verse I apprehend he means that the habitual indulgence of vainglory is utterly inconsistent with the possession of genuine Christianity. Humility is a leading trait in the character of every genuine Christian. He knows and believes that he is guilty before the God of heaven exceedingly, and he feels that he is an ignorant, foolish, depraved creature, that of himself he is nothing, less than nothing, and vanity. Feeling thus his insignificance as a creature, and his demerit and depravity as a sinner, he is not — he cannot be — vainglorlous. Whatever he is that is good, he knows God has made him to be. Whatever he has that is good, he knows God has given him. The falls of others excite in him not self-glorification, but gratitude.

(John Brown, D. D.)

The Self-Deception of Self-Conceit

W.F. Adeney

Galatians 6:3

For if a man think himself to be something, when he is nothing, he deceives himself.

A truism, yet such that, while everybody is ready to apply it to his neighbour, few are wise enough to take it home to themselves. By the very nature of the case it is always ignored where it fits most aptly. Hence the need of insisting upon it.

I. THERE ARE STRONG INDUCEMENTS FOR FORMING AN UNDULY FAVOURABLE OPINION OF ONE'S SELF. Self-knowledge is a difficult acquisition. We cannot get the right perspective. The effort of turning the mind in upon itself is arduous. Then we are inclined to take imagination and desire for direct perception, i.e. to think we possess qualities which we only picture in thought; or to measure our faculties by our inclinations, to suppose that the wish to do certain things carries with it the power. E.g. an enthusiast for the violin is likely to suppose he can handle the instrument musically before other people are of that opinion. The very habit of thinking about ourselves causes a growing sense of self-importance. Moreover, by an unconscious selection we are led to dwell on the favourable features of our own characters, and leave out of account the unfavourable.

II. A HIGH OPINION OF ONE'S SELF IS COMMONLY FOUND TO BE ASSOCIATED WITH A LOW CONDITION OF REAL WORTH. Not invariably, for we sometimes find men of high endowments painfully self-assertive, either because they know that their merits have not been duly recognized, or because their vanity has been excited by the applause of their friends. Such cases reveal a weakness, and strike us as peculiarly unfortunate, for the men of worth would be wiser to wait for the acknowledgment which their merits by themselves will ultimately command had they but patience enough, or at the worst should be above caring overmuch for any such acknowledgment. Still, the merit may be real. In most cases, however, it is those who are least who boast the loudest. The man of little knowledge thinks he knows everything; wide knowledge reveals the awful vastness of the unknown, and impresses profound humility. So the holiest man is most conscious of his own sinfulness. At best, too, what right have we to think much of ourselves when all we have comes from God-our natural abilities as gifts of Providence, our spiritual attainments as graces of the Spirit?

III. AN UNDUE OPINION OF ONE'S SELF IS NOTHING BUT SELF-DECEPTION. It cannot long impose upon others. The world is not inclined to attach much weight to a man's own evidence in favour of himself. (Hypocrisy, or the deliberate effort to deceive others, is out of the question here, as that implies a knowledge of the falseness of our pretensions, while we are now considering the honest belief in them.) Such self-deception is unfortunate,

(1) because it will put us in a false position, incline us to make wrong claims, and to attempt the unattainable, and so result in disastrous failure;

(2) because it precludes the endeavour to improve ourselves;

(3) because it destroys the Christ-like grace of humility;

(4) because it provokes the ridicule, scorn, or even enmity of others. - W.F.A.

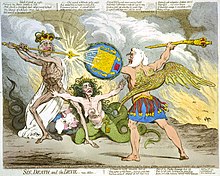

One day Narcissus, who had resisted all the charms of others, came to an open fountain of silvery clearness. He stooped down to drink, and saw his own image, and thought it some beautiful water-spirit living in the fountain. He gazed, and admired the eyes, the neck, the hair, the lips. He fell in love with himself. In vain he sought a kiss and an embrace. He talked to the charmer, but received no response. He could not break the fascination, and so he pined away and died. The moral is, Think not too much nor too highly of yourself.

John Brown, D. D.

Galatians 6:3

For if a man think himself to be something, when he is nothing, he deceives himself.

These words admit of two different interpretations, according as you connect the middle with the first or with the last clause.

1. If we connect the middle clause with the first one, as our translators have done, the meaning is, If a man think himself to be a Christian of a high order, while he either is not a Christian at all, or, at any rate, a Christian of a very inferior order, he commits an important mistake and falls into a hazardous error. The man who supposes himself arrived at the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ, when in reality only a babe in Christ, deceives himself, and throws important obstacles in the way of his own improvement. In their own estimation they have little to learn, while the truth is, they have learned but little. But the mistake is much more deplorable when a man flatters himself into the belief that he is a Christian, perhaps a Christian of the first order, while in reality he is not a Christian at all. The thing is quite possible — I fear not uncommon. We pity the poor maniac mendicant who thinks himself a king; we pity the man who has persuaded himself he is a man of wealth, while in reality he is in immediate hazard of bankruptcy; we pity the man who is assuring himself of long life, when he is tottering on the brink of the grave; but how much more to be pitied is the man who thinks himself secure of the favour of God, and of eternal happiness, while in reality the wrath of God is abiding on him, and a miserable eternity lies before him! No kinder office can be done to such a person than to arouse him from his state of carnal security, to undeceive him, to convince him of his wants while they may be supplied, of his danger while it may be averted. A woe is denounced against such as are thus at ease in Zion.

2. Perhaps, however, the apostle's meaning is, "If any man think he is something, he deceiveth himself, for he is nothing." The apostle is cautioning the Galatians against a vainglorious disposition; and in this verse I apprehend he means that the habitual indulgence of vainglory is utterly inconsistent with the possession of genuine Christianity. Humility is a leading trait in the character of every genuine Christian. He knows and believes that he is guilty before the God of heaven exceedingly, and he feels that he is an ignorant, foolish, depraved creature, that of himself he is nothing, less than nothing, and vanity. Feeling thus his insignificance as a creature, and his demerit and depravity as a sinner, he is not — he cannot be — vainglorlous. Whatever he is that is good, he knows God has made him to be. Whatever he has that is good, he knows God has given him. The falls of others excite in him not self-glorification, but gratitude.

(John Brown, D. D.)

The Self-Deception of Self-Conceit

W.F. Adeney

Galatians 6:3

For if a man think himself to be something, when he is nothing, he deceives himself.

A truism, yet such that, while everybody is ready to apply it to his neighbour, few are wise enough to take it home to themselves. By the very nature of the case it is always ignored where it fits most aptly. Hence the need of insisting upon it.

I. THERE ARE STRONG INDUCEMENTS FOR FORMING AN UNDULY FAVOURABLE OPINION OF ONE'S SELF. Self-knowledge is a difficult acquisition. We cannot get the right perspective. The effort of turning the mind in upon itself is arduous. Then we are inclined to take imagination and desire for direct perception, i.e. to think we possess qualities which we only picture in thought; or to measure our faculties by our inclinations, to suppose that the wish to do certain things carries with it the power. E.g. an enthusiast for the violin is likely to suppose he can handle the instrument musically before other people are of that opinion. The very habit of thinking about ourselves causes a growing sense of self-importance. Moreover, by an unconscious selection we are led to dwell on the favourable features of our own characters, and leave out of account the unfavourable.

II. A HIGH OPINION OF ONE'S SELF IS COMMONLY FOUND TO BE ASSOCIATED WITH A LOW CONDITION OF REAL WORTH. Not invariably, for we sometimes find men of high endowments painfully self-assertive, either because they know that their merits have not been duly recognized, or because their vanity has been excited by the applause of their friends. Such cases reveal a weakness, and strike us as peculiarly unfortunate, for the men of worth would be wiser to wait for the acknowledgment which their merits by themselves will ultimately command had they but patience enough, or at the worst should be above caring overmuch for any such acknowledgment. Still, the merit may be real. In most cases, however, it is those who are least who boast the loudest. The man of little knowledge thinks he knows everything; wide knowledge reveals the awful vastness of the unknown, and impresses profound humility. So the holiest man is most conscious of his own sinfulness. At best, too, what right have we to think much of ourselves when all we have comes from God-our natural abilities as gifts of Providence, our spiritual attainments as graces of the Spirit?

III. AN UNDUE OPINION OF ONE'S SELF IS NOTHING BUT SELF-DECEPTION. It cannot long impose upon others. The world is not inclined to attach much weight to a man's own evidence in favour of himself. (Hypocrisy, or the deliberate effort to deceive others, is out of the question here, as that implies a knowledge of the falseness of our pretensions, while we are now considering the honest belief in them.) Such self-deception is unfortunate,

(1) because it will put us in a false position, incline us to make wrong claims, and to attempt the unattainable, and so result in disastrous failure;

(2) because it precludes the endeavour to improve ourselves;

(3) because it destroys the Christ-like grace of humility;

(4) because it provokes the ridicule, scorn, or even enmity of others. - W.F.A.

One day Narcissus, who had resisted all the charms of others, came to an open fountain of silvery clearness. He stooped down to drink, and saw his own image, and thought it some beautiful water-spirit living in the fountain. He gazed, and admired the eyes, the neck, the hair, the lips. He fell in love with himself. In vain he sought a kiss and an embrace. He talked to the charmer, but received no response. He could not break the fascination, and so he pined away and died. The moral is, Think not too much nor too highly of yourself.

Job 34

New International Version

1Then Elihu said:

2“Hear my words, you wise men;

listen to me, you men of learning.

3For the ear tests words

as the tongue tastes food.

4Let us discern for ourselves what is right;

let us learn together what is good.

5“Job says, ‘I am innocent,

but God denies me justice.

6Although I am right,

I am considered a liar;

although I am guiltless,

his arrow inflicts an incurable wound.’

7Is there anyone like Job,

who drinks scorn like water?

8He keeps company with evildoers;

he associates with the wicked.

9For he says, ‘There is no profit

in trying to please God.’

10“So listen to me, you men of understanding.

Far be it from God to do evil,

from the Almighty to do wrong.

11He repays everyone for what they have done;

he brings on them what their conduct deserves.

12It is unthinkable that God would do wrong,

that the Almighty would pervert justice.

13Who appointed him over the earth?

Who put him in charge of the whole world?

14If it were his intention

and he withdrew his spirita and breath,

15all humanity would perish together

and mankind would return to the dust.

16“If you have understanding, hear this;

listen to what I say.

17Can someone who hates justice govern?

Will you condemn the just and mighty One?

18Is he not the One who says to kings, ‘You are worthless,’

and to nobles, ‘You are wicked,’

19who shows no partiality to princes

and does not favor the rich over the poor,

for they are all the work of his hands?

20They die in an instant, in the middle of the night;

the people are shaken and they pass away;

the mighty are removed without human hand.

21“His eyes are on the ways of mortals;

he sees their every step.

22There is no deep shadow, no utter darkness,

where evildoers can hide.

23God has no need to examine people further,

that they should come before him for judgment.

24Without inquiry he shatters the mighty

and sets up others in their place.

25Because he takes note of their deeds,

he overthrows them in the night and they are crushed.

26He punishes them for their wickedness

where everyone can see them,

27because they turned from following him

and had no regard for any of his ways.

28They caused the cry of the poor to come before him,

so that he heard the cry of the needy.

29But if he remains silent, who can condemn him?

If he hides his face, who can see him?

Yet he is over individual and nation alike,

30to keep the godless from ruling,

from laying snares for the people.

31“Suppose someone says to God,

‘I am guilty but will offend no more.

32Teach me what I cannot see;

if I have done wrong, I will not do so again.’

33Should God then reward you on your terms,

when you refuse to repent?

You must decide, not I;

so tell me what you know.

34“Men of understanding declare,

wise men who hear me say to me,

35‘Job speaks without knowledge;

his words lack insight.’

36Oh, that Job might be tested to the utmost

for answering like a wicked man!

37To his sin he adds rebellion;

scornfully he claps his hands among us

and multiplies his words against God.”